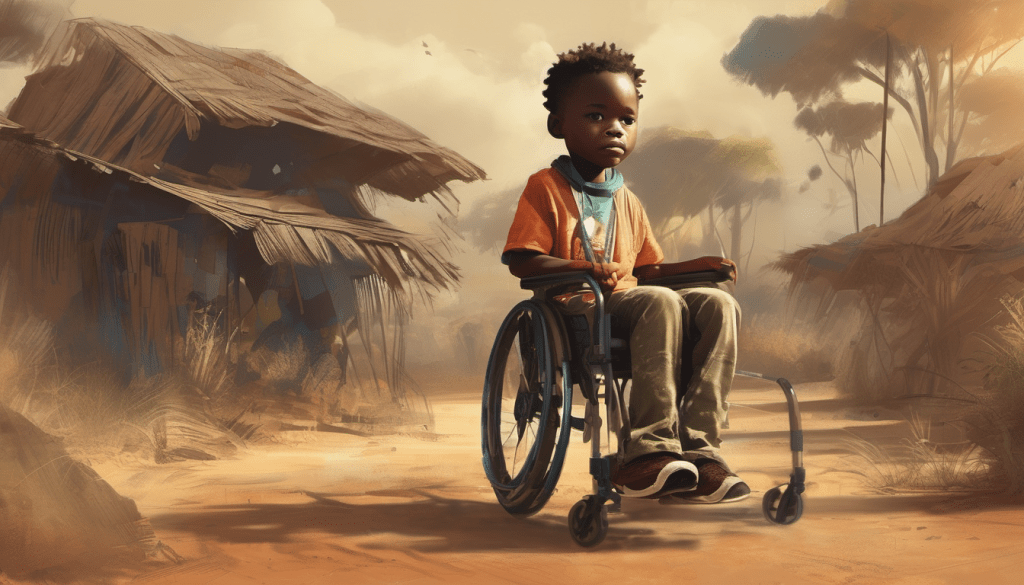

In Lesotho, the promise of education, a fundamental human right, remains unfulfilled for many children with disabilities. Despite legislative and policy measures aimed at fostering inclusive education, numerous obstacles persist, hindering these children’s access to quality schooling.

Another year, another story on the Lesotho government’s failure to fulfill its commitment to provide quality education for children with disabilities. Education for all? Or for only those who are able-bodied?

Frustrated parents and caregivers of children with disabilities continue to flood to social media platforms in search of guidance and assistance. Some plead for funds to acquire specialized wheelchairs for their children, while others appeal for basic necessities for neglected children whose parents are either absent or struggling to provide.

Then there are those who cannot even articulate their child’s condition, lacking the knowledge to understand the nature of their disability. All they know is that they are disabled.

“My nine year old son suffers from osteoporosis. His condition is deteriorating to the point where I fear he may lose the ability to walk,” shared one Mother said anonymously on a popular facebook page, Lilaphalapha. “I’ve tried to take him to Hlotse, Motebang Hospital, they referred me to Tshepong Public Hospital, where I was advised to give my son milk and eggs. I have tried to make sure that the child eats as per the recommendation, and he even goes for check ups, but I can see that he’s only getting worse,” she lamented.

Continuing, she added,“ I have taken him to a school for children with disabilities because they have physio, but there hasn’t been any change. Please, can you help me with a place where I can take him before he injures himself.

The cost of a new wheelchair in neighboring South Africa, ranges from R3, 600 to R15, 000 and beyond. For children, the prices seem to be steeper with the most affordable options starting at R6, 391. While better deals may be found, the adage “You get what you pay for” still rings true.

These prices are exorbitant, especially when considering that the cheapest wheelchair exceeds the monthly salary of many Basotho.

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) sheds light on these and other challenges in their recent briefing paper (2023), “Failed Implementation: Lesotho’s Inclusive Education Policy and the Continued Exclusion of Children with Disabilities.” Through extensive research and interviews with stakeholders, including parents, educators and government officials, the ICJ exposes the systemic failures undermining inclusive education in Lesotho.

Tim Fish, Hodgon, ICJ’s Legal Advisor on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, emphasizes the universality of the right to education, asserting that disability should not preclude access to learning. Yet, Lesotho’s efforts fall short, with a glaring gap between policy intentions and practical realities.

“Every child has the right to attend school. A disability should not change this. Lesotho’s obligations in terms of the right to inclusive education require it to transform its education system to ensure that all children with disabilities can access equal, quality and accessible education.” said Tim Fish Hodgson, ICJ’s Legal Adviser on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Mulesa Lumina, ICJ’s Legal and Communication Associate Officer, echoes this sentiment, highlighting the frustration among educators and parents over the lack of progress. Despite initiatives from organizations like the Lesotho National Federation of the Disabled (LNFOD) and UNICEF Lesotho, the systemic challenges persist, perpetuating exclusion and inequality.

“Many of the problems raised in the paper are well known to education ministry officials and staff at inclusive and special schools. Our research reveals a deep frustration in these environments with the lack of progress in implementing the Inclusive Education Policy.” said Mulesa Lumina, ICJ Legal and Communications Associate Officer.

The ICJ’s findings reveal a litany of issues plaguing inclusive education in Lesotho, including the exclusion of children with disabilities from the majority of schools, persistent stigma and social exclusion, inadequate funding, and infrastructural shortcomings. Moreover, legislative inconsistencies and gaps exacerbate the problem, further entrenching systemic barriers to education.

According to the findings by UNICEF (2023) Report on Children and Young People Living with Disabilities in Lesotho, the consultations with the staff from the centers for children with disabilities reveal distressing accounts of neglect, abuse and societal marginalization that children with disabilities experience.

Many parents find it hard to accept their children with disabilities, struggling with stigma and shame. Some confine their children indoors, neglecting their needs and well-being.

Center staff explained that there are instances where parents “do not care about their children.” They remarked that “They [parents] are happier when their children are away from them, and they care less about their safety and wellbeing.” In fact, when schools close, some parents never show up for their children and they do not provide them with basic needs, and such neglect places children at risk.

Some children even “get so miserable when they are supposed to go home, they do not like going back to their communities.” Because some families live in poverty, food, clothes and other basic needs are a problem when the children return home.

And even if the children do go to school, there are still so many obstacles to overcome, from inaccessible infrastructure to scarcity of mobility aids, which perpetuates a cycle of exclusion and vulnerability.

According to the ICJ (2023), children with special educational needs are particularly vulnerable to exclusion from the educational system and struggle to access quality education. Despite the presence of six special schools and 15 inclusive schools in Lesotho, many children with disabilities, likely remain out-of-school or attend institutions that cannot accommodate their special needs.

Frustrated and overwhelmed parents often turn to local social media platforms for advice or financial support, yet many lack the means to act upon the guidance offered. Lesotho’s socio-economic landscape compounds their challenges, forcing some parents to leave their children unattended for extended periods while they are at work.

Despite legislative frameworks and policy commitments, the gap between rhetoric and reality for children with disabilities and their parents is disheartening.

And despite ratifying the CRPD in 2008, it was only recently that the rights of persons with disabilities became a key priority for the government with the enactment of the Persons with Disability Equity Act of 2021. This pivotal legislation established the Persons with Disability Advisory Council in 2023, aimed at providing equal opportunities and recognition of rights for persons with disabilities.

Additionally, the Act mandates the Ministry of Finance to establish a Disability Public Fund to support disability programs and services, including grants for persons with severe disabilities.

The government did pilot the Disability Grant in 2020 in Butha-Buthe, where 222 people with disabilities were given LSL400 on quarterly basis. The grant is meant to provide support to hundreds of persons with disabilities who are unable to work.

The recommendations put forth by the ICJ underscore the urgent need for action. From raising awareness and allocating resources to enhancing teacher training and legislative reforms, a multifaceted approach is required to address the systemic deficiencies undermining inclusive education.

As Lesotho grapples with these challenges, it is imperative that concerted efforts are made to uphold the rights of children with disabilities and ensure their access to quality education. Only through collective action and unwavering commitment can Lesotho truly deliver on its promise of inclusive education for all.

Leave a comment